Ph.D. FML

Posted by fxckfeelings on March 19, 2020

There’s a good reason that every “quest” story, from Luke Skywalker’s to Harry Potter’s, ends with said quest being satisfying fulfilled; namely, a hero who fails doesn’t seem like much of a hero at all. That’s why it can feel so painful if you dedicate years to your education—making a long series of educational sacrifices for the sake of a career, acquiring mountains of debt, forgoing all the pleasures that your paycheck-receiving contemporaries are enjoying—only to discover that your would-be career sucks and your epic quest has been in vain. Since it happens to good people who are making reasonable decisions, however, there should be no shame, self-recrimination, or rumination on mistakes if you must find ways to use your hard-won knowledge and discipline to figure out what to do next. Then you haven’t actually failed; you’re just on a longer hero’s journey than bargained for.

-Dr. Lastname

I have a Bachelors in Psychology and a Masters in Counseling and Psychology, and I am a Ph.D. candidate but I need to leave my program to move back home and take care of my mom. I spent some time kinda feeling bad about leaving this “elevation” of the Ph.D. behind, but I also knew, in a way, that this whole field was bullshit. My question then is, if my field of study is stupid—even after all the years I’ve dedicated to it—what should I do now? I want to play a part in the future understanding of mental health, which will no doubt be informed by science, but I’m not sure that what I’ve been studying will provide that (i.e., the stuff I’ve studied is nothing like the approach in your books). My goal is to be a part of the mental health field with an approach that makes sense to me (and the academic one does not).

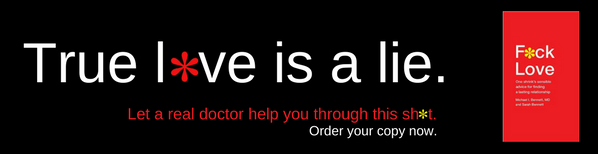

F*ck Love: One Shrink’s Sensible Advice for Finding a Lasting Relationship

It’s tough to find that, after investing so much time and effort in completing a masters and starting a Ph.D., you don’t actually agree with or value the lessons you’ve spent all those years learning, but it happens. As much as we might like to think that with hard work and a willingness to learn and compromise, we can fit in anywhere, it’s just not true.

Some people may be gifted and unique while also lacking some common quality that is necessary for success in the field that initially appeals to them. When things don’t work out, they falsely blame themselves or their fields for being failures. But that just makes it that much harder for them to learn a useful lesson about what didn’t work for them and apply it to their future path.

The fact that you are interested in psychology and have spent years in classrooms suggests that you immersed yourself in theory and, possibly, experimental work. If that’s the case, you’ve also discovered that those aspects of psychology lack meaning for you. But academic psychology and applied psychology—i.e., the tools you use as a therapist—aren’t exactly the same thing.

So if you remain interested in mental illness and treatments and haven’t had an opportunity to work with patients, try to take a job as a mental health aide on a psychiatric inpatient unit or day hospital. The pay isn’t great but you’ll get a chance to see how treatment works, how clinicians think about it, and what it means to be a psychologist in practice, not just theory. After six months, you’ll know whether you’ll want to get a clinical degree and continue your education in a direction that suits you better.

As for your interest in science and mental illness, don’t expect it to be satisfied, regardless of what you study, at least not in the immediate future. It’s a good wish, but we don’t yet have the science to tell us how much of the brain works, let alone why one person’s depressive or schizophrenic symptoms differ from another’s or why one medication works on an individual when another, very similar medication does not. So if you like working with the mentally ill, get used to doing so while the science is still very much a work in progress.

You’ve identified real interests and acquired a good deal of relevant knowledge, so don’t let your frustration with psychology as you’ve encountered it in academia discourage you or cause you to label your efforts a failure. In the course of your education, you’ve learned that you want to focus your studies elsewhere. It’s a valuable lesson, and one you can use to move forward in a direction that will utilize all your knowledge and expand it in a more meaningful way.

STATEMENT:

“I feel like I’ve wasted years of study and that caring for my mother is much more meaningful than pursuing knowledge that I no longer respect, but I’ve also discovered that I can work hard, think critically, and continue to have interests that can and should shape the way I will make a living. I will continue to be proud of what I’ve accomplished and remember that my obligation to find meaningful work is always worthwhile.”